Resident Artist Research Project

4. Free Art In the Woods & at the Bell

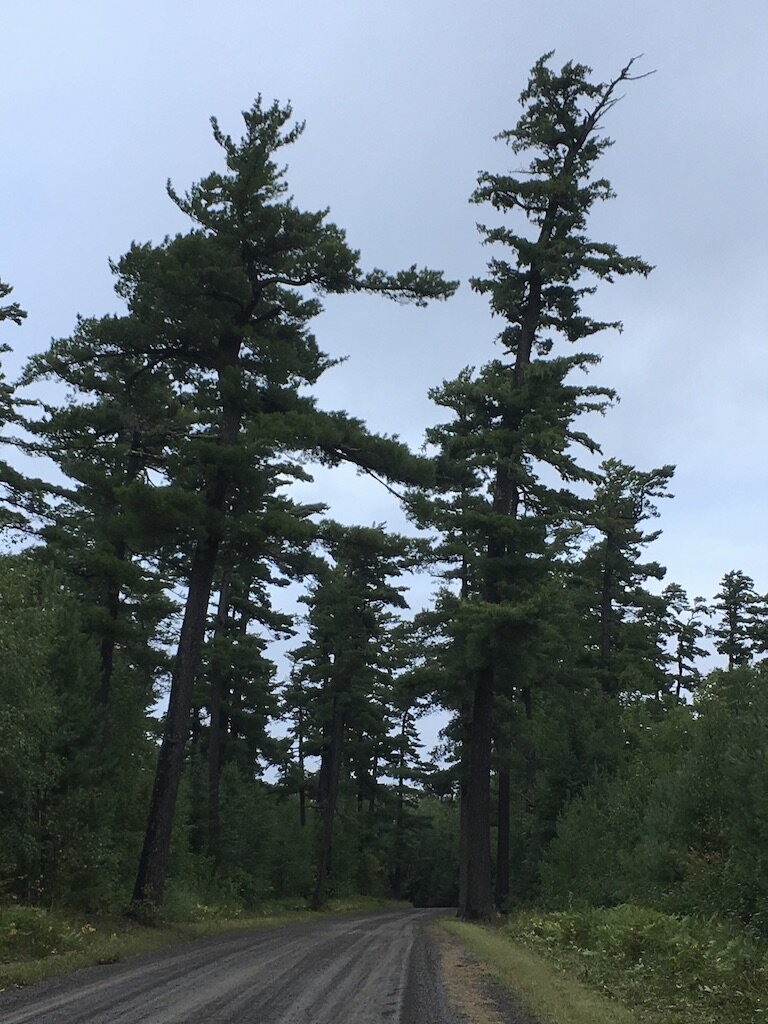

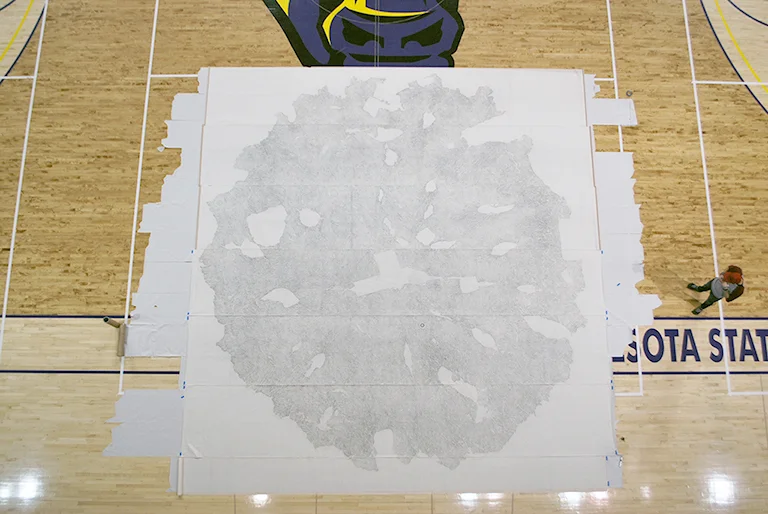

I created a geocache project for the Bell Residency to get work outside, accessible, and available to anyone up for a walk in the woods. The prints reference the theme of connection spread throughout the residency work. In this case, connection to the forest, its roots, and its fruits. The image was conceived in the pandemic springtime. One of those moments where everything was just right despite our human reality. The morning sun raking the forest floor, turkeys gurgling nearby, morels poking through the leaves, the forest miraculously starting up again.

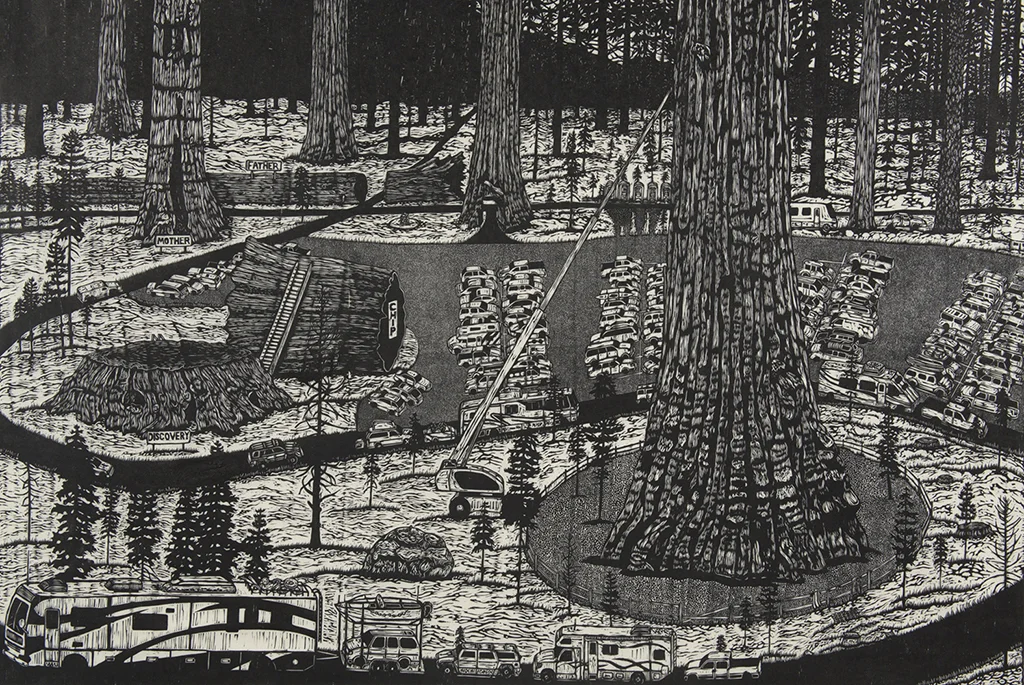

I was also thinking about the sharing economy of the forest, the fungal networks sharing nutrients below ground, collaborations between species, and the complexity of interaction around us that we can only begin to glimpse. Plants and fungi have been growing and knowing for hundreds of millions of years before us. We evolved in their world. A world that has nourished us. How can we protect it, reforest it, reflood it, release it from our grasp a little?

For the cache, I hollowed out a few sections of a basswood tree that recently fell behind my house. These husks blend into the landscape and house the prints from the elements. Two separate caches of prints are at the Seven Mile Creek County Park between Mankato and St Peter, MN and one will be installed on the Bell Museums grounds soon.

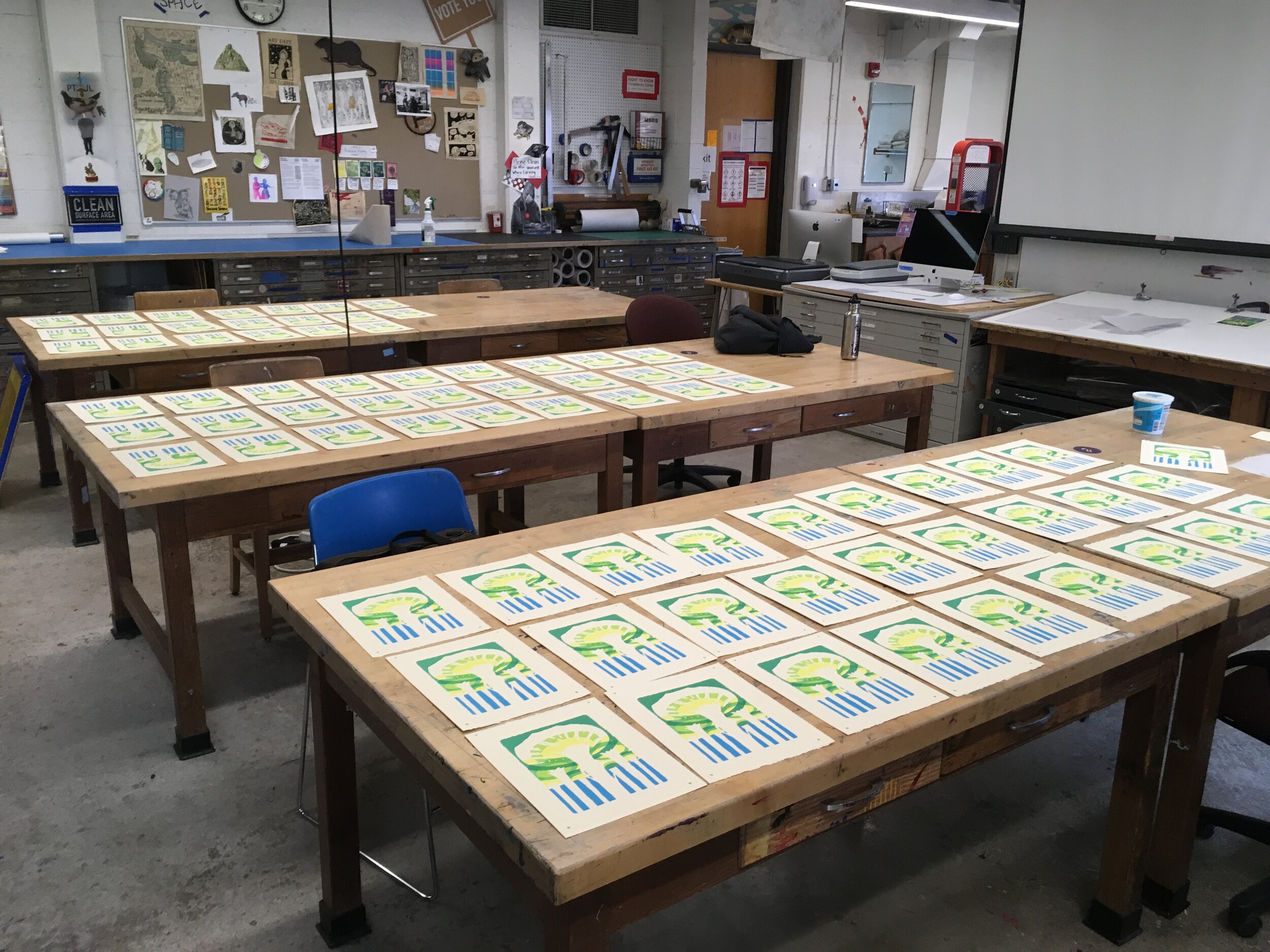

The print is called “Connection.” It consists of five layers of screenprinting with a key(black) relief printed layer. I printed an edition 60 prints to give away in 3 locations. This short video summarizes the hand-printing processes that went into the finished work.

Thanks:

THANK YOU to Cellar Press and Anne Makepeace at the Grand Center for Arts and Culture in New Ulm for access to their Vandercook press and their outstanding studio.

THANK YOU to the Bell Museum and the McKnight Foundation for making this work possible.