The Late Great White Pine, and the Superior National Forest

The Late Great Pine Forests & Death by a Billion Cuts, two layer woodcut print with waxed paper, 40”x120”

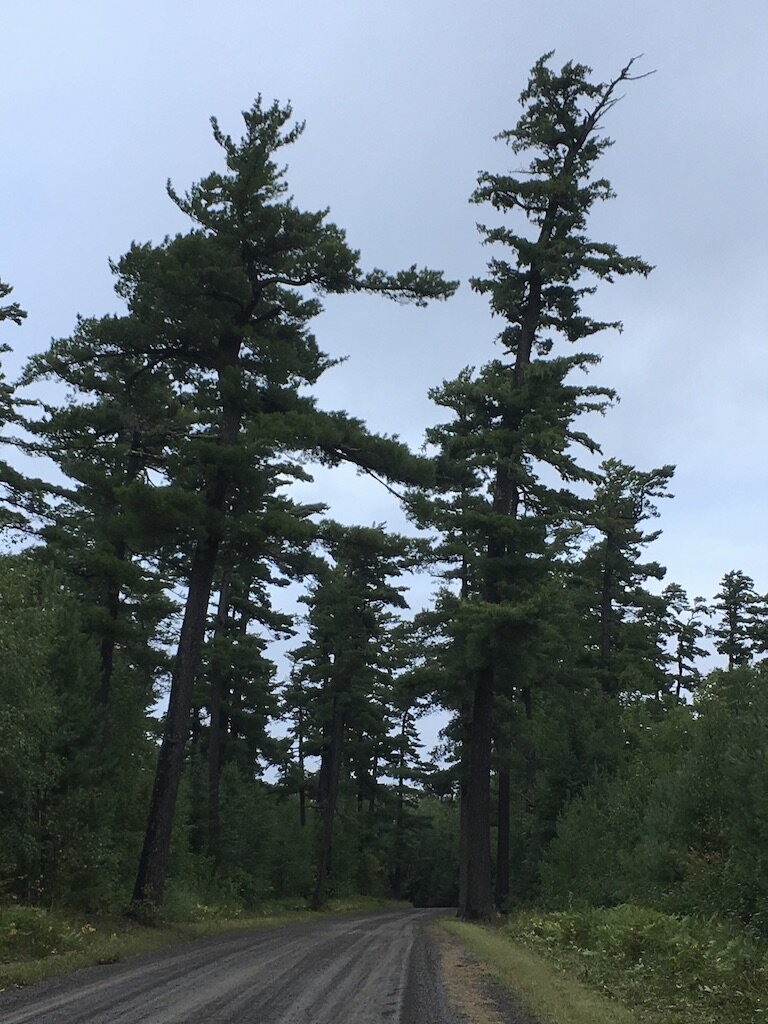

Visiting a small patch of remaining old-growth, it’s easy to imagine how the vast white pine ecosystems of Minnesota once rivaled the complex drama of any old-growth forest. They were an infinite resource. They were a cultural resource. As these great forests brought wealth to settler communities at the turn of the century, Indigenous peoples watched the great rivers carry their homeland to the sawmill in less than 15 years.

The Late Great White Pine Forest. Color woodcut, 40”x120”

The first significant saw mill was in Stillwater, and one of the biggest log jams in the history of the country happened here as all that white pine lumber floated down the St. Croix River to the mill. Jams were broken up by hand and with dynamite.

Death by a Billion Cuts. Woodcut, 40”x120”

Like much of the north-eastern United States, the upper Midwest, and southern Canada, Northern Minnesota once had an enormous acreage of dominate pine forest. These massive trees, many over 400 years old, grew tall and straight, and were strong and light weight. They were the perfect lumber for any number of construction projects from timber framing to ship masts. More than 100 years before logging began in Minnesota, The Eastern White Pine even played a role in the American Revolution.

As the royal navy of Great Britain had exhausted European forests for ship building, they discovered the straightness, and flexibility of the white pine as a superior mast wood. The Crown coveted the white pine forests so much that they wanted all the best specimens for themselves. The King of England issued a charter near the turn of the 17th century stating that white pines with a diameter of 24in or larger were the property of the crown, and would be shipped to England to supply the navy. King George even sent his men to walk the forests marking the mast-trees with three hatchet strokes commonly called the “King’s Broad Arrow.”

Unsurprisingly, the settlers continued cutting and selling the lumber, infuriating the Crown, and in part, contributing to the American Revolution. Some of the first American flags, revolutionary war flags, even celebrated the white pine in their iconography.

After the coastal east was combed, loggers continued west to places like Michgan, Wisconsin, and ultimately Minnesota. Hiking the 300-mile Superior Hiking Trail, canoeing the boundary waters, traveling through the large forest ecosystems of northern Minnesota - all this land held the westernmost reaches of the eastern white pine. And while there are a handful of old growth survivors along the way, these white pine forests have been largely replaced with faster growing/short lived species like birch, aspen, cottonwood.

Old-growth Pockets in Northern Minnesota

White pine portraits. Woodcut prints.

The Superior National Forest grove near Two Harbors - White Pine Trail

This short, 1000 feet, loop has an interpretive trail through old-growth with nine stops. It’s about a half hour inland from Two Harbors.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/recarea/superior/recreation/recarea/?recid=77755&actid=50

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5194351.pdf

The Arrowhead Trail & the Gunflint Trail

There is a nice grove straddling the arrowhead trail on your way to McFarland Lake or the terminus of the Superior Hiking trail. These trees are said to be quite old, 185 years, but their growth has been stunted due to an abundance of bedrock. The spot is worth checking out if you are in the Grand Marais area. The white pines tower over the rest of the forest. You can also find a nice patch driving along the Gunflint Trail.

The Lost 40

This 40 acre plot in north Central Minnesota was never logged. Due to a survey error, the land was thought to be a lake, and was passed over. There are old-growth red and white pine. It’s amazing to see the thriving ecosystem and think about the long-evolved relationship between the under-story and canopy. A trail leads through the forest and one of the largest red-pines in the state is along the way.

The Superior Hiking Trail

Through-hiking the 300 miles Superior Hiking Trail from Duluth to Canada promotes an intimate engagement with the forests of the past and present. There are patches of old white pine scattered throughout. In most cases, the survivors are growing in extreme locations (the steep edge of a ravine for example) where logging would have been too difficult. There is also quite a bit of red pine, but much of this seems to be planted for later harvests. The southern stretches of the trail are mixed conifer and hardwood forests, while the northeastern most sections carry through the only boreal forest ecosystem in the lower 48.

These forests were clear-cut steadily from the late 1800s to the 1930s. New tree populations took hold, deer (who like to eat young pines) populations grew, invasives like blister rust moved in, natural fires diminished, and now the tree that once dominated struggles to reach maturity. We now have completely different ecosystems with more erosion, quickly shifting forests, different flora and fauna, and not much in the way of long-lived trees that can establish a canopy system and a stable environment.

There is a lot of planting going on, especially in parks and national forest land. Plots of forests are mechanically cleared as natural fires would have cleared them in the past. Seedlings are planted and fenced off to protect them from deer.

Some Reccomended Reads:

American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation - Eric Rutkow

North Country: The Making of Minnesota - Mary Lethert Wingerd

The Hidden Life of Trees - Peter Wohlleben

The Overstory: A Novel - Richard Powers