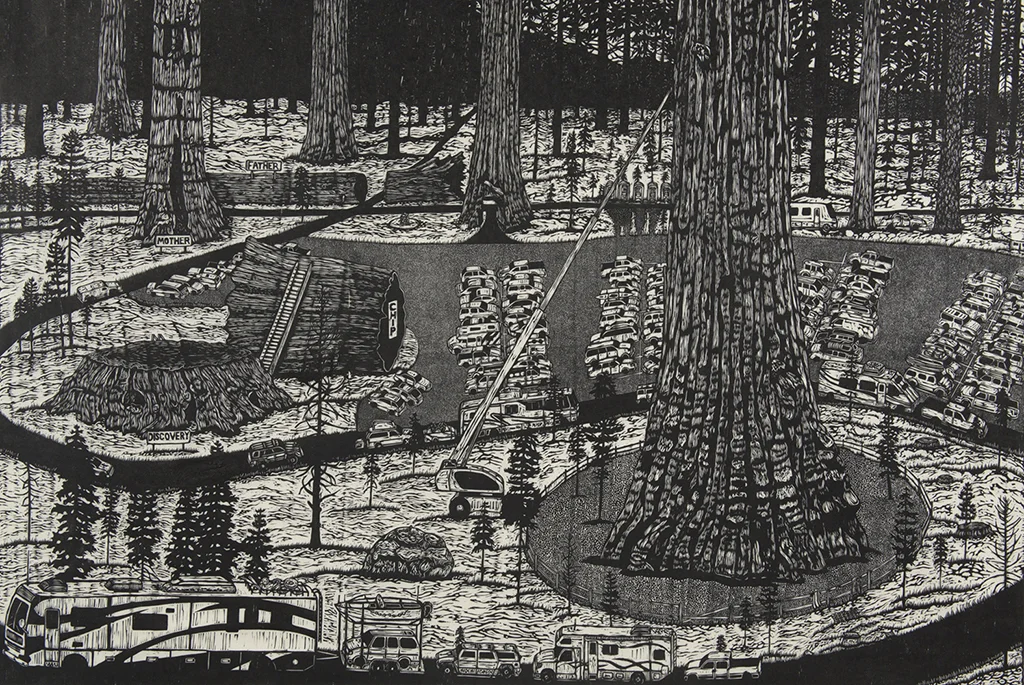

My prints and drawings explore specific places in the American landscape. While roadside attractions, accessible vistas, the tallest peaks, and the largest trees might illustrate ideas of American superiority, or the evolution of place from the sacred to the profane, they are also symbols that provoke preservation movements and celebrate community individuality. Recently, I have been interested in the Calaveras Grove of Big Trees.

I began a body of prints and drawings in 2013 to visually tell the story of this giant sequoia grove in northern California from the initial destruction of its largest trees in 1851 to the state of the grove today. As the first sequoia grove exploited by Euro-Americans, as a catalyst in the conservation movement, and today, as a grove celebrating the largest species on the planet, the Calaveras Grove of Big Trees conveys a gripping narrative. The exploitation, ignorance, destruction, and conservation efforts of this historic spot are emblematic of the westward expansion of European immigrants across this country. As the American population swells and continues to exploit the landscape, the Calaveras story is important to reflect upon.

This body of work chronicles the destruction of the Discovery Tree, the Mother of the Forest, and the Pioneer Cabin Tree. It also more broadly celebrates the giant sequoia as a species, its unique place in the Sierra, and the threats it has faced in the past / potential threats it may face in the future.

print detail

The Grove was initially “discovered” by gold minors in 1852 when a hunter, Augustus T. Dowd, for a water/mining company in nearby Murphy's, CA, stumbled upon the grove while chasing a wounded grisly. One year later, the Union Water Company Staked their claims on the land. The giant tree that first enthralled Dowd, was quickly coined The Discovery Tree, the name its stump still carries today.

The Discovery Tree was said to be 300 feet tall with a diameter of 25 feet. For a relatively young giant sequioa, 1244 years old, this tree was of similar proportions to what we consider the largest living giant sequioa today(The General Sherman Tree - 2500 years old). An adjacent creak fed its root structure and the nearby prairie provided an abundance of light for the accelerated growth of the tree.

The miners stripped the bark off the Discovery Tree to a height of 10 feet, and hauled it 150 miles to San Fran to reassemble in an indoor space to turn a profit on ticket sales. In the age of PT Barnum and the circus sideshow, the San Franciscans believed it a farce, that the bark had been cut from several large redwood trees. To prove their claim, the minors decided to fell the tree and cut a slab from the trunk to transport to San Francisco. So began the first felling of a giant sequoia.

They used their 12-foot mining pipe augers to worm into the trunk from all sides. Twisting the giant corkscrews by hand, it took 10 men 25 days to bore sufficiently through the trunk. Even then, the symmetry of the tree kept it erect. The tree fell days later when a windstorm came through and finished the job. The stump was quickly turned into a dance floor, and the trunk, a bowling alley.

Jon Muir famously wrote upon visiting the grove:

Soon after the discovery of the Calaveras Grove one of the grandest trees was cut down for the sake of its stump! The laborious vandals had seen ‘the biggest tree in the world,’ then, forsooth, they must try to see the biggest stump and dance on it

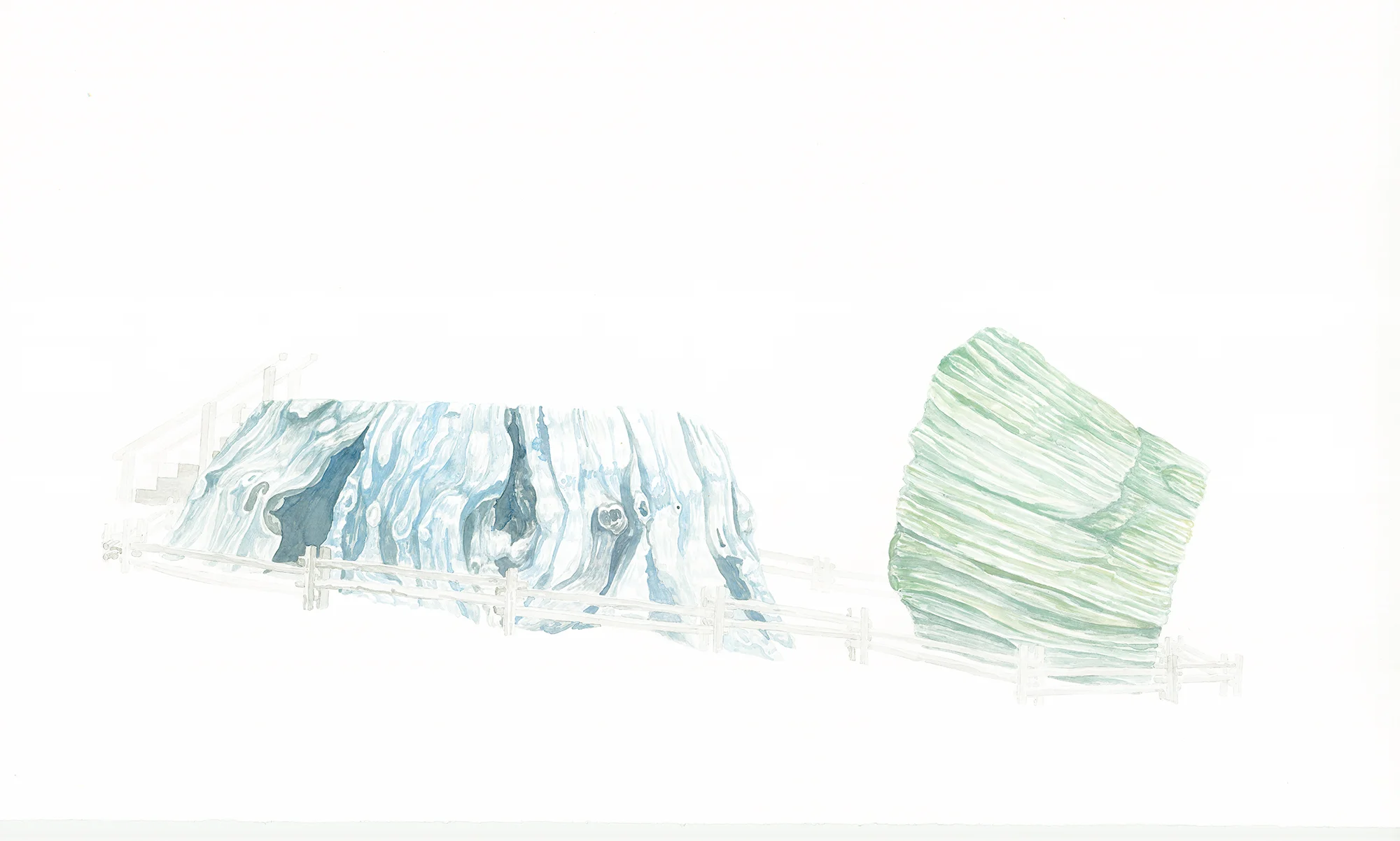

Another tree, “mother of the forest,” was the new largest sequoia in the grove. In 1853, two years after felling the discovery tree, the bark of mother of the forest was removed to a height of 116 feet by gold miners from Michigan. The removed bark enabled these industrialists to transport the idea of these trees around the world. The bark of the tree ironically burned up in London’s Crystal Palace’s in 1866.

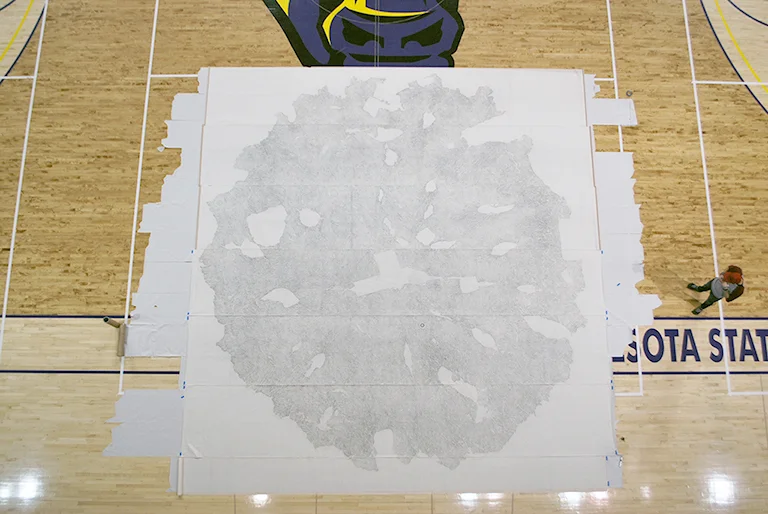

In the summer of 2014, I was issued a scientific collections permit by the superintendent of the park. This permission allowed me to spend eight, 10-12 hour days completing a 1:1 ratio rubbing of the Discovery Stump, as it exists today, 160 years after it was felled. I additionally completed two smaller rubbings for the park staff to utilize in their interpretive programming, and I have gifted the park a relief print about the grove to display in their new education center. The experience connected me with hundreds of park visitors, established new friendships, and served to better educate myself and park visitors to the contemporary relevance of this story.

By performing an edition of relief rubbings from the stump, I can achieve a similar, yet non-invasive, function to shipping the bark of Mother of the Forest around the world. The democratic nature of printmaking and the portability of paper, will allow Midwestern viewers to see firsthand the scale and contours of the stump. As a photograph cannot provide any real understanding of these giants, the print may also serve as a direct link for those who have not made it to California themselves.