Pace

Each time I walk a footpath, whether stamped in the snow between parking lots, a deer trail in tall grass, or an extended hike for months in the woods, I find magic and metaphor in the collective path. Started by one then maintained through collective use, the walking path is a living history between past and present and a thriving link between species.

The pace of foot travel & river travel foster intimate connections to the land. Our species evolved to travel this way, to carry the supplies of survival, and to develop extensive knowledge of plants and animals.

Whether walking a long-distance backpacking trail, foraging for edibles, or growing some vegetables and walking a bit in the woods, it’s deeply human to have personal connections to the land. These links are beneficial to our health as well as the health of the land that sustains us. As we make decisions about landscape spaces and energy consumption, it is also critical that political and spiritual leaders have tangible connections to the land around them.

The Light of the Green Tunnel. Color woodcut print. 20x16”

The Trail

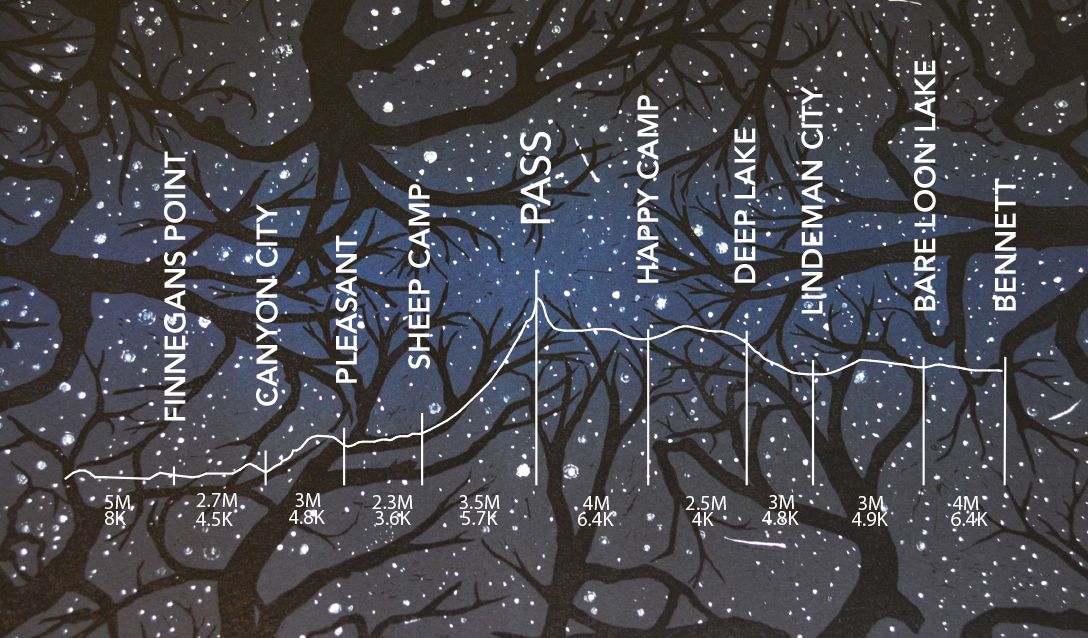

The Chilkoot Trail is a footpath charged with history, varied ecosystems, and intense beauty. Packed into only 33 Miles, the trail carries through swaths of rainforest, alpine, and boreal forest ecosystems. From glacial streams to bright alpine lakes, from mossy ferns to sand dunes, the trail holds intense drama and no monotony.

This footpath was long utilized by Tlingit and Tagish people as a trading route from the pacific to the headwaters of the great Yukon River. A route of travel and trade, of goods and culture, from the coast to the interior. Artifacts show that people have inhabited this area for at least 9,000 years.

Near the turn of the 20th century, this trail became a sprawling artery toward the distant northern gold fields in the Yukon Territory. In 1897, a few ships arrived to northwestern ports in Seattle and San Francisco bearing significant loads of “Klondike” gold. News quickly spread global with snowballing exaggerations and false truths. The promise of easy wealth during a depressed economic time contributed to the massive mix of newcomers.

Chilkoot Pass - US/Canada Border. Photo of photo

Miners packed a year’s worth of supplies and provisions (1500pounds/person) up the rugged Chilkoot Trail and over the infamous pass to a collection of lakes that form the headwaters of the Yukon River. Here they cut the forest to make boats and paddled the additional 450 miles down river to the gold fields in what is now the Dawson City area in the Yukon Territory.

Of the 100,000 persons who stampeeded north in search of gold, some 30,000 arrived to Dawson City, Yukon. Quickly growing larger than Seattle and Vancouver, Dawson became one of the largest cities in Canada despite its remote location.

Death at the Yukon Headwaters. Screenprint. 22x30”

Bennet Lake - Yukon headwaters. The terminus of the hiking trail and the beginning the paddling trail

Before the significant gold discovery in 1897, the Tr'ondek Hwech'in prospered from the wealth of this land at the confluence of the Yukon and the Tr'ondëk Rivers at a fish camp called Tr’ochëk just across the Klondike River from what is now Dawson city.

After the gold discovery, the Tr'ondëk River became the famous “Klondike” River and Tr'ondek Hwech'in’ people moved 3 miles down the Yukon River to the Jëjik Ddhä̀ Dë̀nezhu Kek´it, or Moosehide, community, named after the iconic rock slide overlooking what is now Dawson City. In recent years, archeological digs have revealed that people have occupied the Dawson City area for at least 11,000 years.

The Great Yukon River Path. Color woodcut print. 16x20”

The Residency

The Chilkoot Trail Artist Residency is a backpacking residency walking the 33 mile trail, tenting at group camp sites, and teaching artist workshops to hikers. This residency is a collaboration between the United States National Parks Service, Parks Canada, the Yukon Arts Center, and the Skagway Arts Council. These groups collectively select 3 artists annually for the opportunity. The route starts in the United States at the Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park and ends at Canada’s Chilkoot Trail National Historic Site.

Deep Lake. One of the many Alpine / Sub-alpine lakes that gather and flow toward the headwaters of the Yukon

I used my time to explore beyond the trail, to re-hike favorite sections, to write & draw extensively, and to teach relief printmaking workshops to hikers in route. While most hike the trail in a few days, I was lucky enough to settle into life on the trail. I enjoyed great weather and swam almost daily in the bright blue lakes on the Canada side.

120 year old stumps - Sheep Camp area - rain forest. Here, stampeeders clear cut for winter warmth. Sheep Camp is the last campspot below the timberline. It is estimated that 6-8,000 people occupied Sheep Camp during the height of the rush.

120 year old stumps - Bennet Lake area - boreal forest. Here, miners clear cut the forest for fuel and boat lumber to carry their outfits some 500 miles down river to Dawson City.

The more time spent on the Chilkoot, the more I became interested the recovery of the forest from the gold rush. I felt stronger connections to the pre-gold rush footpath than to the narratives of the minors. While all the rusty remains are visually fascinating, I'm not sure the forest will be fully recovered until all the food tins, yukon sleds, and rubber boots have fully broken down and been swallowed by the forest.

In addition to carrying my carving tools and a few woodblocks of my own, I also carried tools, ink, brayers, kozo paper, and woodblocks for artist workshops on the trail. After cooking their dinners, hikers learned the relief carving and printing process in or around campsite shelters. These postcard-like prints allowed hikers to create visual reflections after all the thinking/walking hours they had built up on the trail.

Artist workshop - Lindeman City Camp

Thank You to the Yukon Arts Centre, Parks Canada, the US National Park Service, the Skagway Arts Council, and the Skagway Traditional Council for supporting this project. In addition to these organizations, I’m am grateful to all the wonderful Park Rangers in Skagway & stationed on the trail, as well as the Wardens on the Canada trail side & in Whitehorse.

Please see forthcoming post, Natural and Manufactured Residency, For more reflection on the history, context, and personal experience with relation to Dawson City, YT.